A Summary

Take a look at archival footage recovered from the future to discover how Stanford was transformed by Open Loop University.

Key Details

Historical Notes

The Setting

The phonograph, the telephone, human operated vehicles, carbon emitting fuels—it’s hard to imagine here in 2100 what life might have felt like when that antiquated technology was pervasive. Yet it’s important to try to understand the context of our history, even as we celebrate all that we have become today.

Before neurosocial educators fully understood the cognitive processes surrounding human learning, society sent its young people to college for just a few years, early in their adult lives. They were meant to absorb all the information and skills they would need for the rest of their productive lives, and then burst forth fully formed and equipped to succeed—much like the even older myth of Athena born in full armor, springing from the head of Zeus.

There were early signs that a change was needed.

For example, around 2015, it became clear that only about a quarter of college graduates worked in a field that was directly related to their college major—either students weren’t choosing well, or the majors themselves did not correspond to the new kinds of professions emerging. The advent of online learning showed a taste of the vast hunger for knowledge and skills from unexpected populations at various times over the course of their lives. The frequency with which graduates changed careers now required advanced learning at unpredictable periods throughout an individual’s life.

The Shift

Until its quasquicentennial in 2016, students applied for admission to Stanford around the age of 17, were admitted and conducted their studies for four years from ages 18 – 22. They then graduated and became alumni. Some portion would return a few years later to pursue a graduate degree.

That, strangely enough, was it.

Then, Stanford fully reinvented itself as the first Open Loop University.

Views began to change about the role of higher education over an individual’s life course. The perspective that the university could effectively serve its original mission while continuing to narrowly define the time in one’s life when learning would happen was challenged. Examples of new models started emerging, such as Stanford’s Distinguished Careers Institute – focused exclusively on providing access to Stanford offerings for older adults who had already accomplished at least one significant phase in their professional lives.

The Dean of Admissions conducted an experiment in 2015 to recruit 10 percent of an incoming class using a special “age-blind” process. The results started to

diversify the mixture of student ages on campus, and break down the pre-existing class (year) structures. Students built new cohort experiences to create strong and lasting social connections as they had before. Classroom learning was enriched by both the naïve, bold perspectives of younger-than-average classmates, and the wisdom of the experienced, older ones.

The Open Loop University

By the time it was fully adopted, the new model had some key characteristics. Students applied when they were ready – some earlier, and some later than age 17. Upon enrollment, students received six years of access to residential learning opportunities to distribute across their lives as they saw fit.

Many students chose to concentrate their on-campus stint for a few years on the earlier side, as the social process of maturation within a peer group remained important. Others, freed from social stigma, attached to taking gap years or years “off” during their educations. They dove enthusiastically into applied environments—doing internships and in-country language immersion, reporting back that these experiences sharpened their desire for and ability to select majors and classes that were relevant. Faculty began to report a generally higher level of intellectual engagement from students in their introductory and advanced courses.

From Alumni to Populi

No longer considered alumni, returning students coming back for a mid-career loop took advantage of on-campus course offerings to launch new chapters of their professional lives. They often provided inspiration and insight that accelerated research in labs. Faculty enjoyed new collegial relationships with these accomplished practitioners.

Open Loop pioneer Phil Pizzo once noted, “Where we once had an association of alumni looking fondly back at Stanford as just one time in their lives, we now have a populi of 215,000 ongoing students who know that Stanford is there—and theirs—throughout a lifetime. These students’ deep engagement with the University means we have an activated, distributed Stanford network around the world who are connected whether they are on-campus in residence or not.”

The Achievement

Open Loop University:

- De-stigmatized a range of legitimate patterns of learning (gap years, etc.) so that early-career students used their time and investment in on-campus learning wisely and for greater impact

- Provided a way for older adults to pivot careers with an academic grounding, and to reconnect with a meaningful and energizing social context later in life

- Revitalized Stanford with a broader mix of students by creating on-ramps at many ages; enabled populations traditionally underrepresented at elite institutions to gain greater access once they had time to overcome disadvantaged circumstances

- Developed new operational infrastructure for the University with the ability to handle a more dynamic and shifting on-campus population

- Developed a distributed engagement model to maintain the broader network of Stanford populi

- Capitalized on the remarkable accomplishments of its populi through the invitation to return to campus as expert practitioners.

Exhibit Article Archive

Browse below to search through video archives of the exhibits displayed on May 1st, 2100.

Article 15

Advertisements for Open Loop University

Marketing materials developed and used in publications from 2025-2040

Stanford’s marketing department focused on communicating the new Open Loop system during the 2020s and 2030s. This was part of a strategic initiative to differentiate the Stanford experience and communicate that Stanford produced curious, intellectually vibrant, and agile lifelong learners.

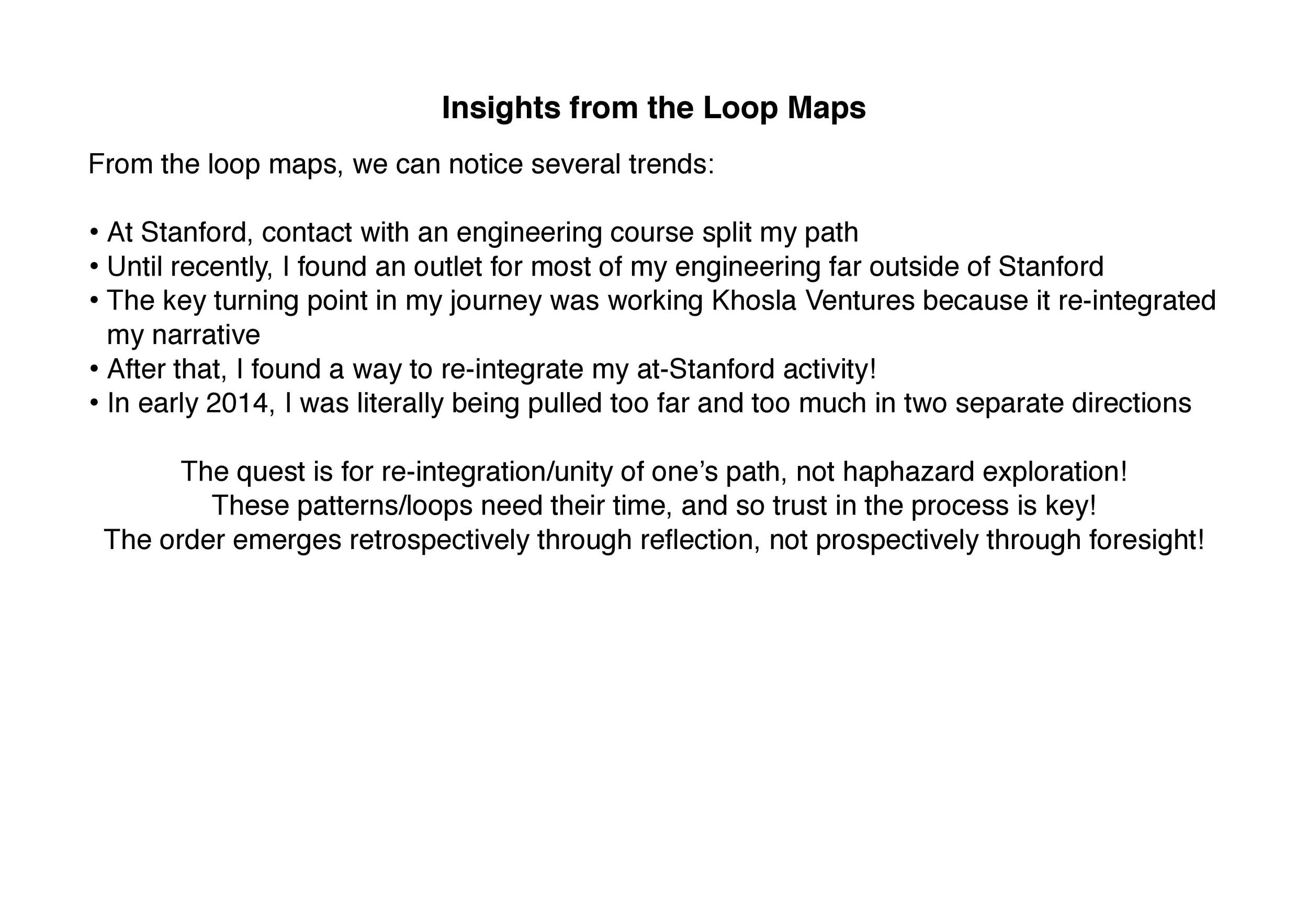

The ads displayed here cover a variety of aspects and benefits of the Open Loop structure, including the archive of loop paths that Stanford curated over time to guide and inspire future students. One successful advertisement highlighted the path journeys of different individuals over their lifetimes. Stanford also began a new campaign when Admissions started recruiting students in 2015, which continued until the eventual closing of the application process in 2035.

Watch Video of Tania Anaissie explain Loop Ads.

Kelly Schmutte explaining Loop Ads.

Loop Ads on display.

VIEW LOOP ADS GALLERY

Article 65

C3 READER

Apple iPad (early “tablet“ device), Kiosk

Cardinal Community Currency, commonly called C3, was a community currency system proposed shortly after Open Loop was announced in 2016. Students were able to spend their credit on everything from courses to coffee on campus, and after completing a Mentorship and/or Teaching C3 Certification, they could begin earning credit back.

Populi could earn C3 by teaching master classes or mentoring students and could spend their C3 on anything from Rose Bowl tickets to MBA tuition.

Faculty were able to earn C3 by teaching courses beyond their appointed requirements and could trade in their earned C3 for additional research funds or sabbatical time.

This is one of the original C3 Readers placed in Tresidder Union during the 2016 pilot program. The user interface allowed students to check their C3 balance with a fingerprint.

Watch Video of Ashish Goel explain Cardinal Community Currency.

Article 35

LOOP ORIGINS

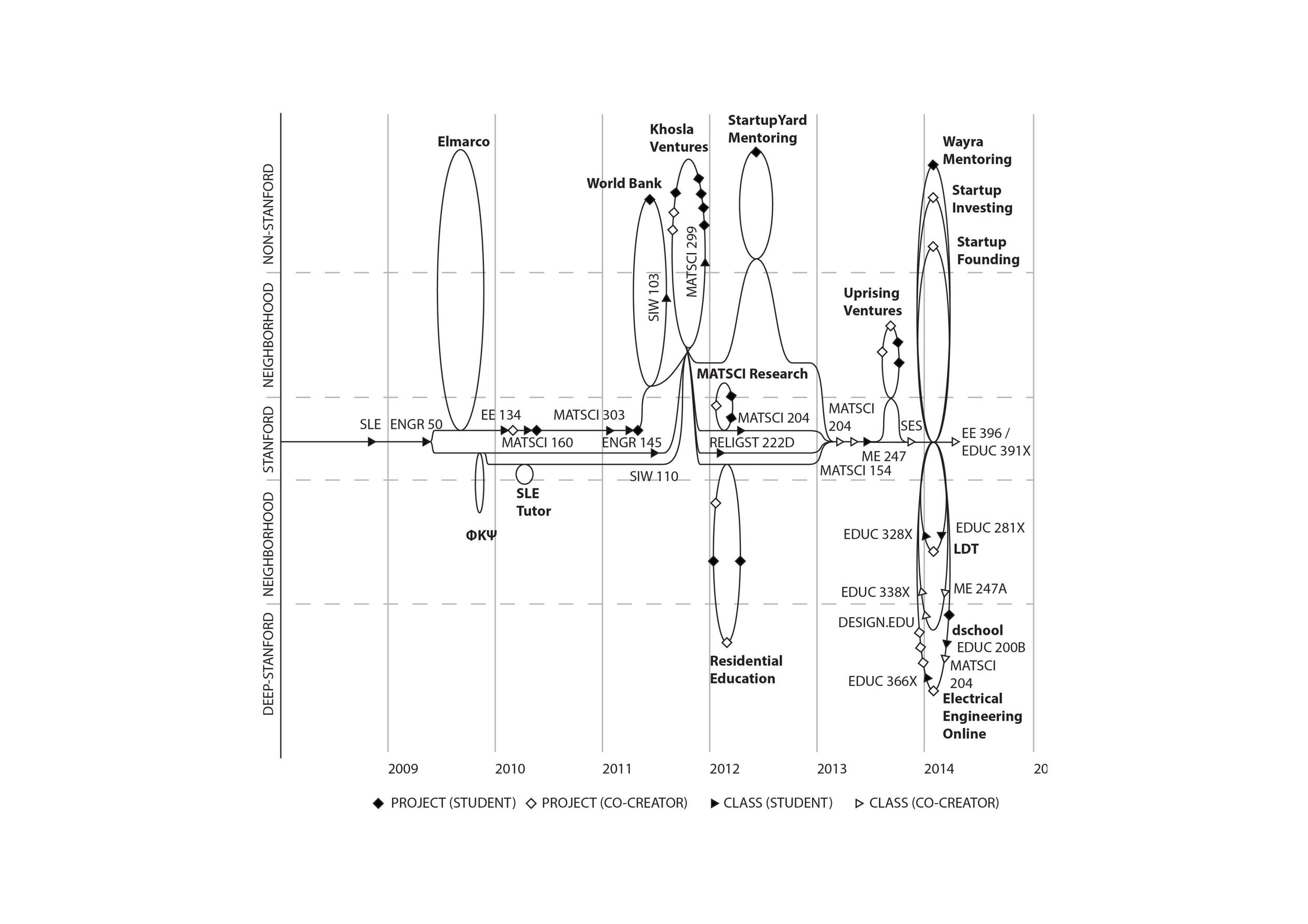

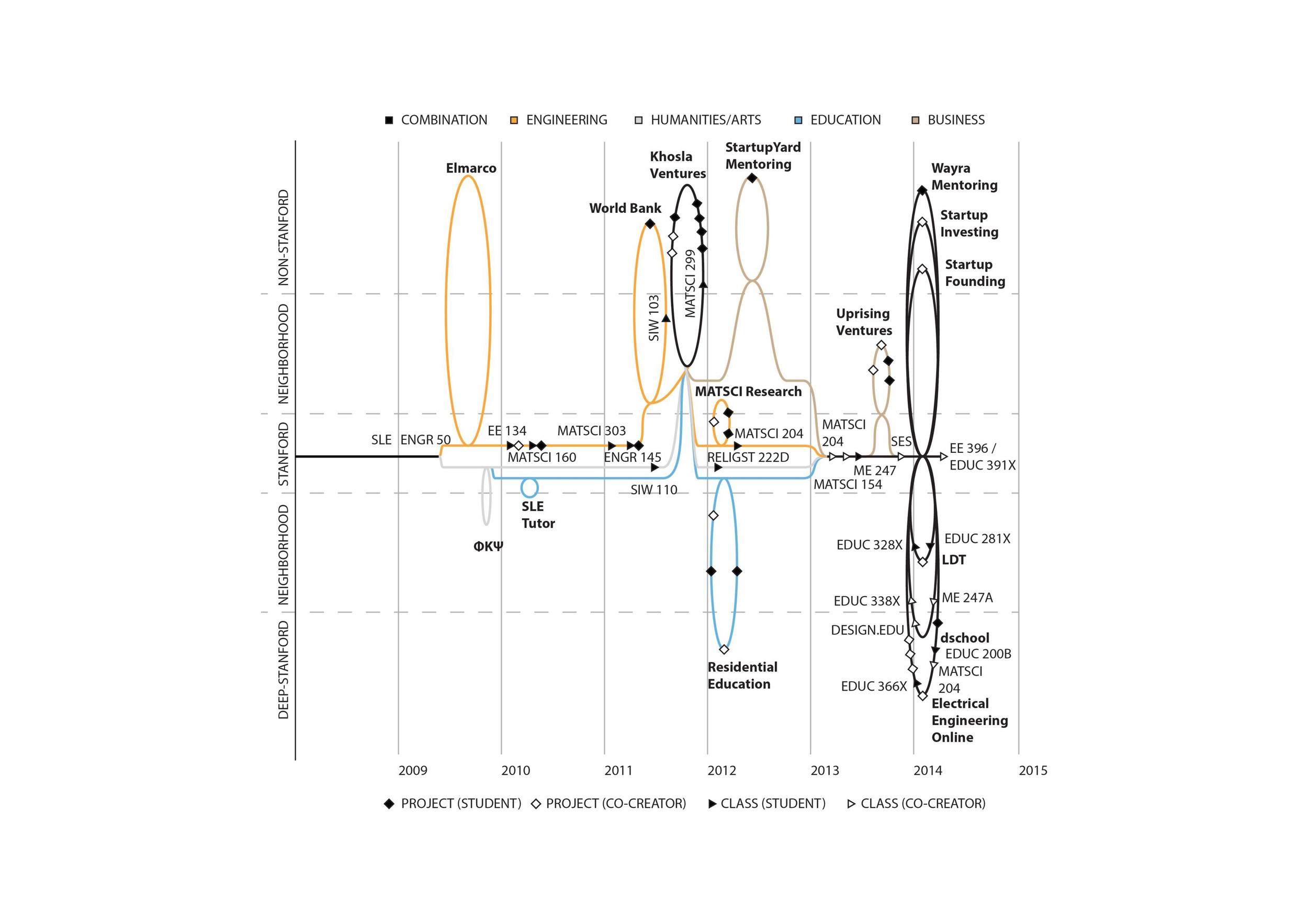

Found notebook pages from early 21st century professor, Petr Johanes

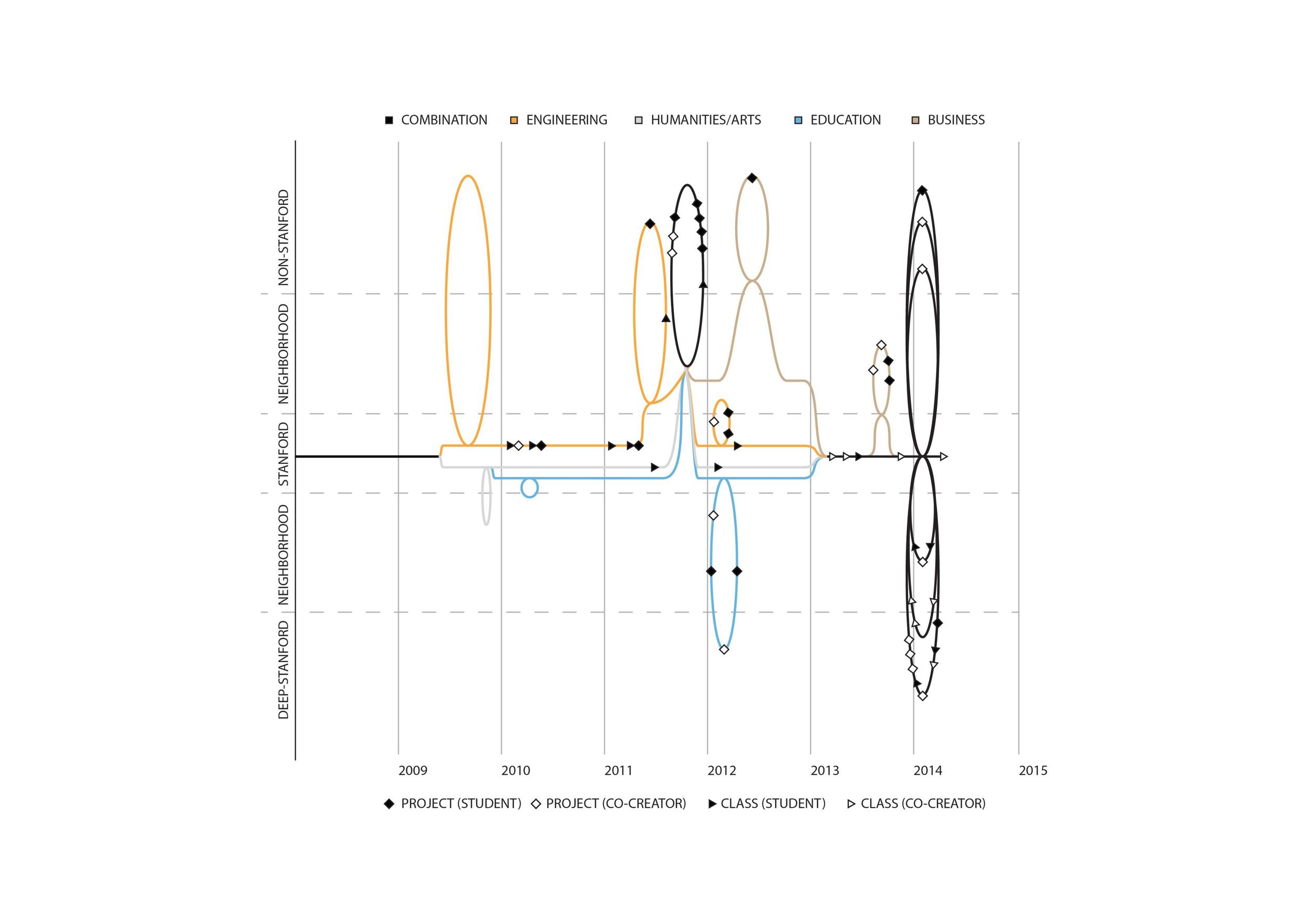

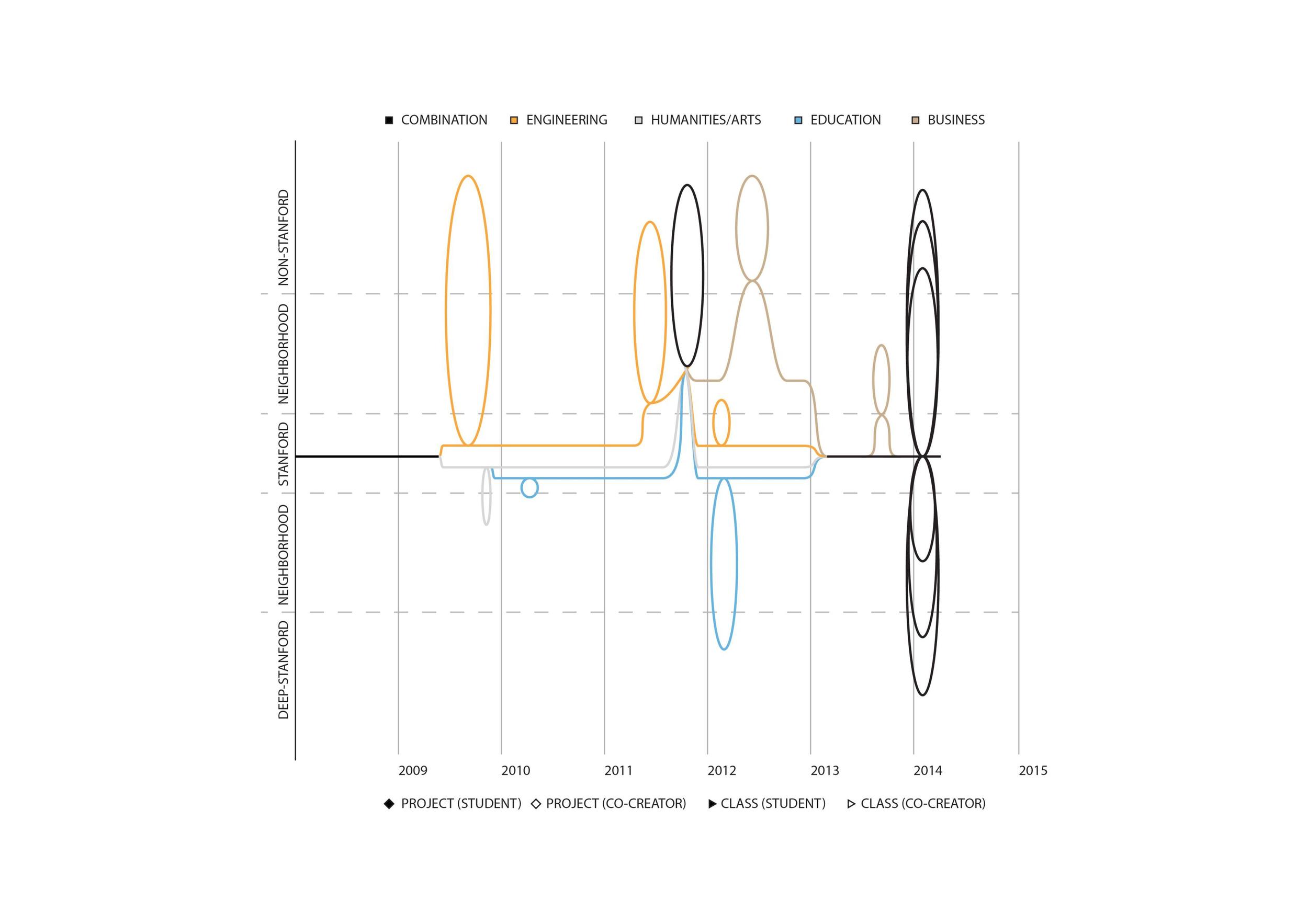

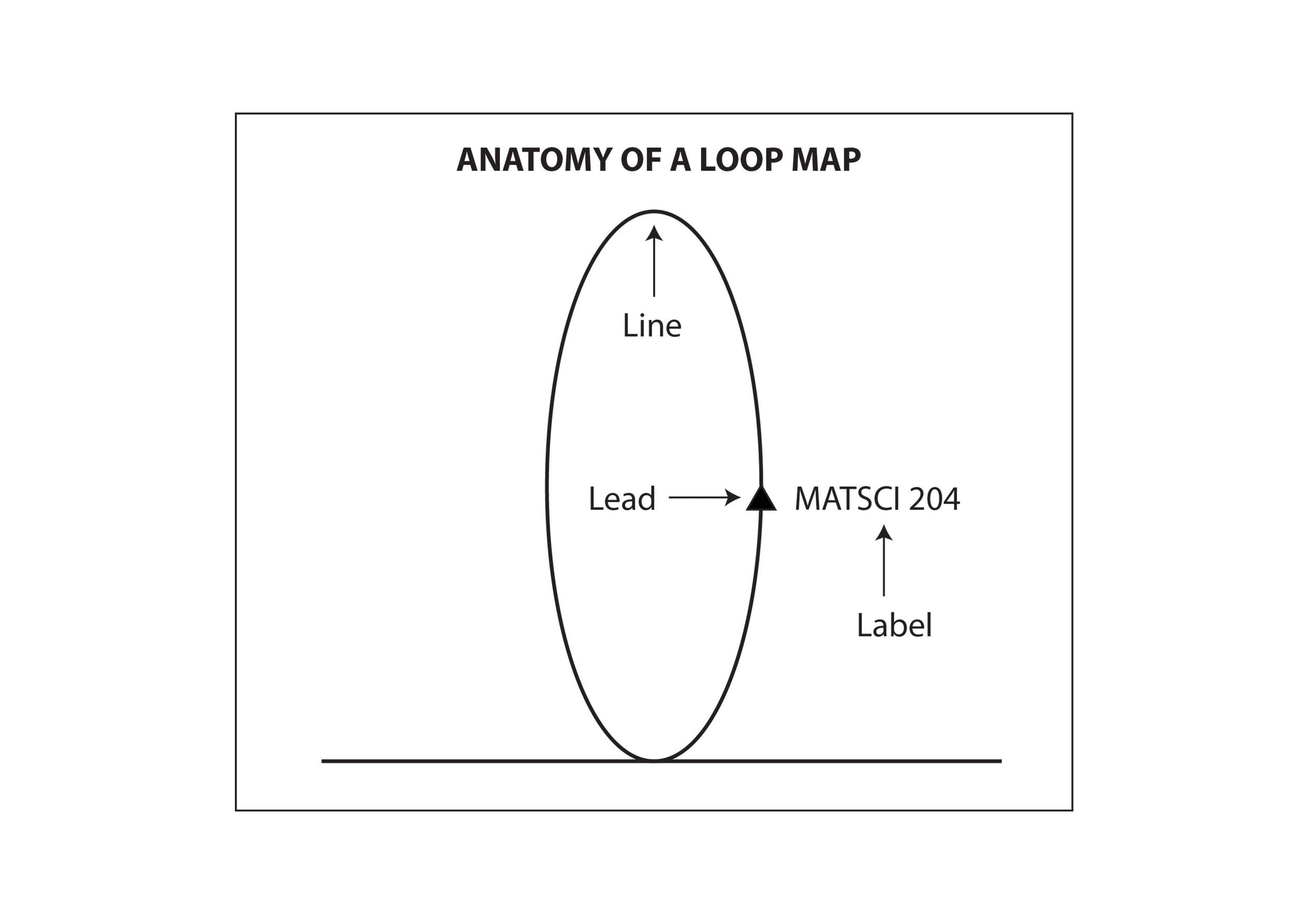

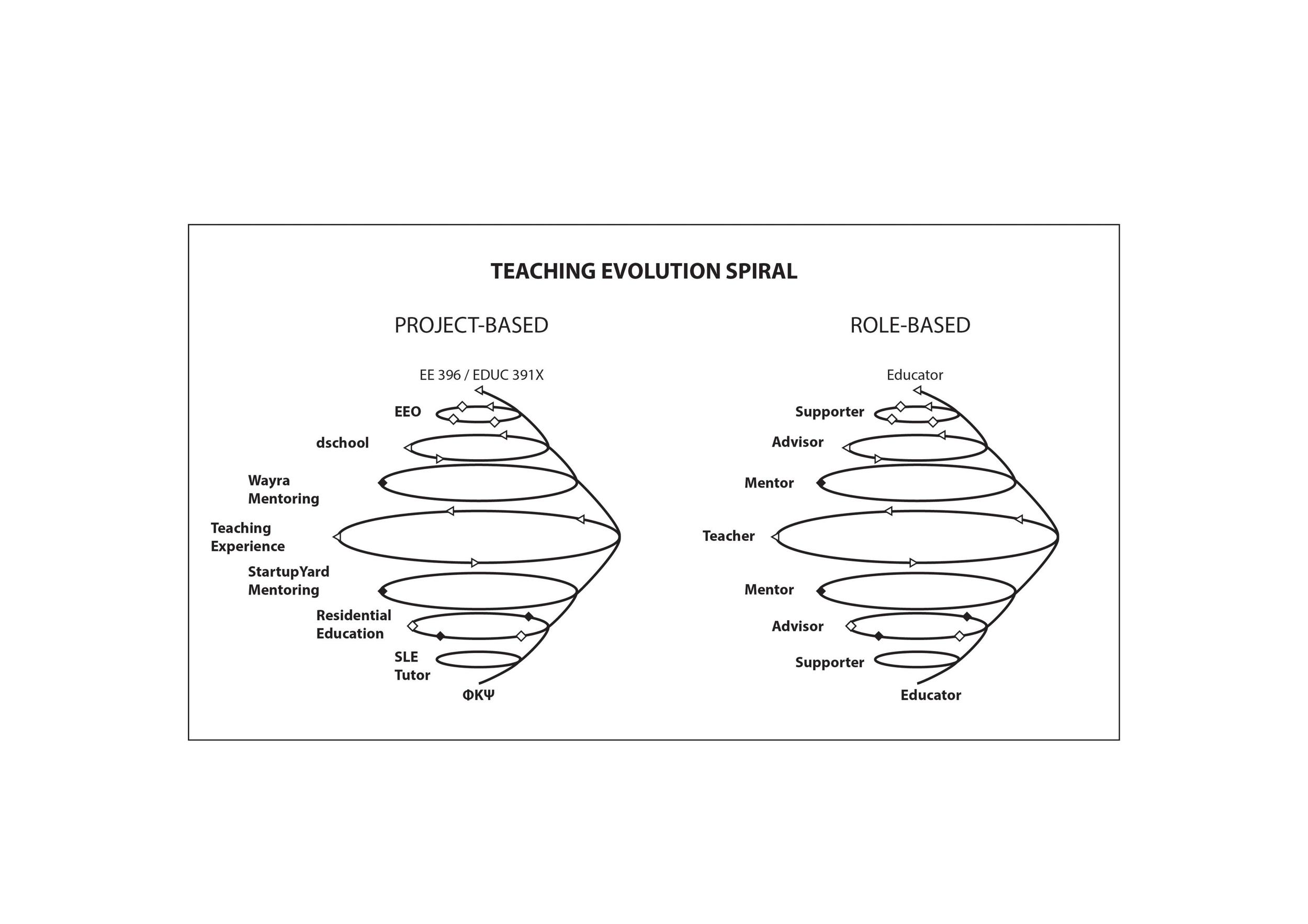

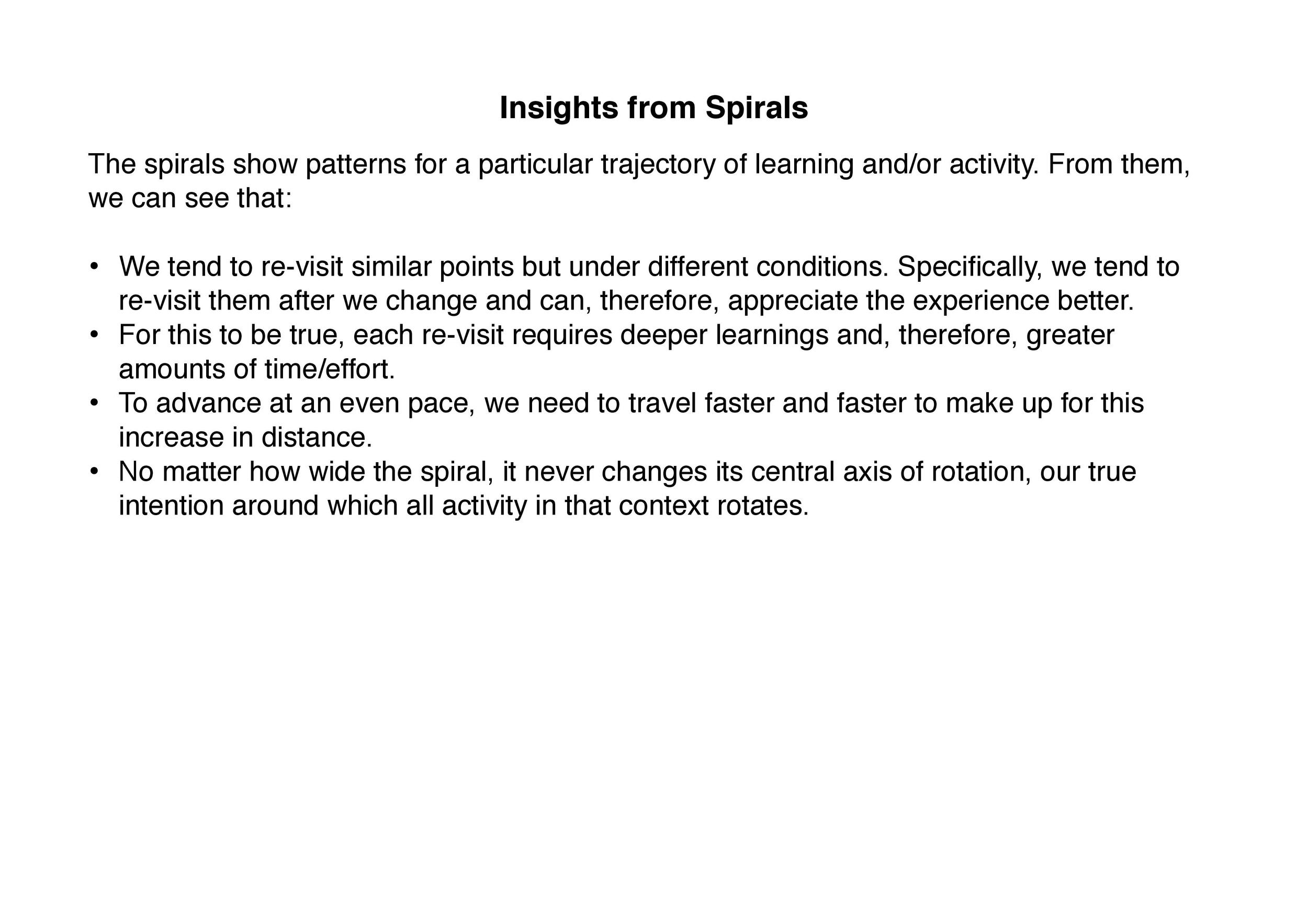

Professor Petr Johanes was deeply involved in the 2015 experiment led by the Dean of Admissions that admitted 10% of the following year’s incoming class using “age-blind” admissions. This would eventually become Open Loop University.

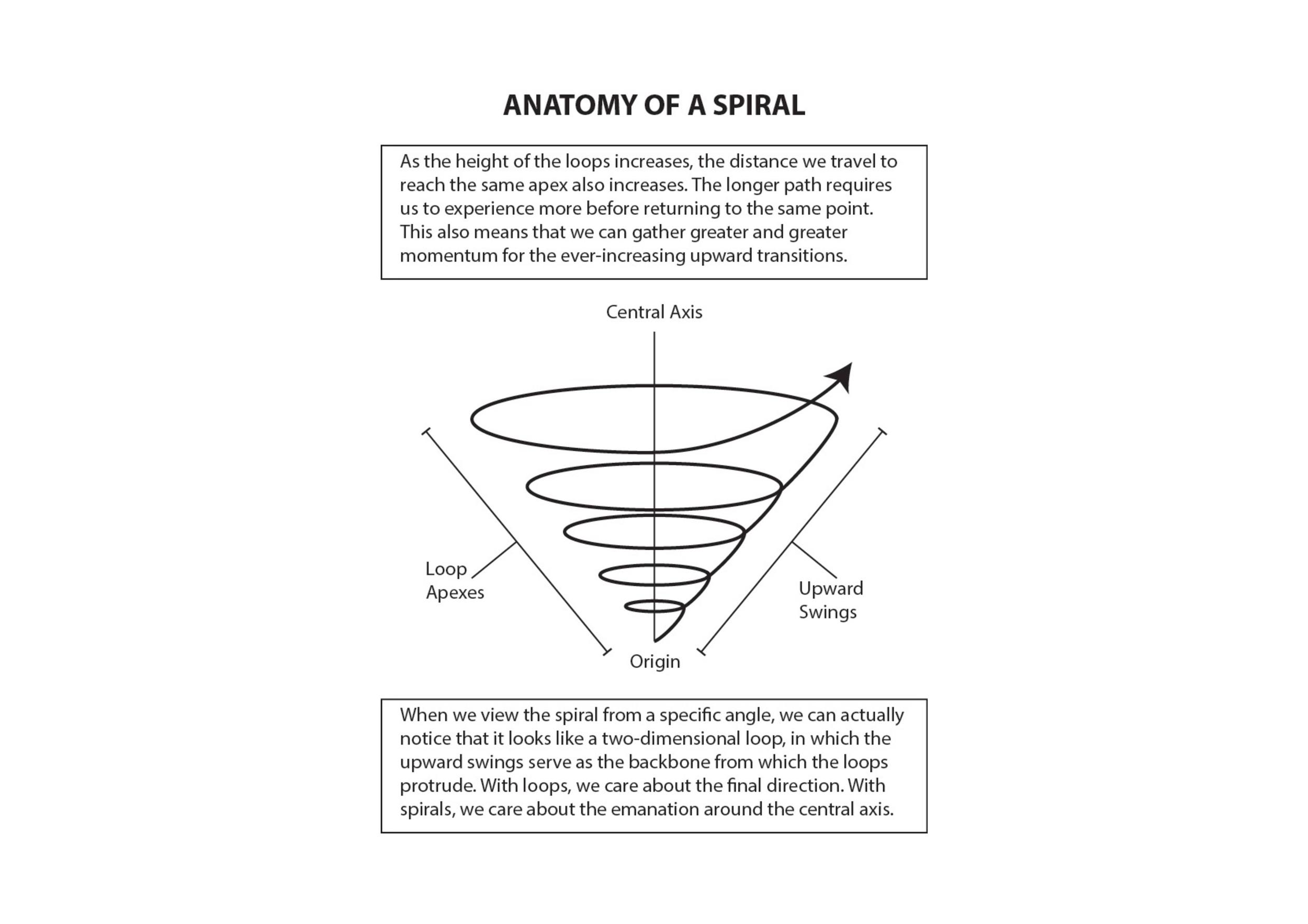

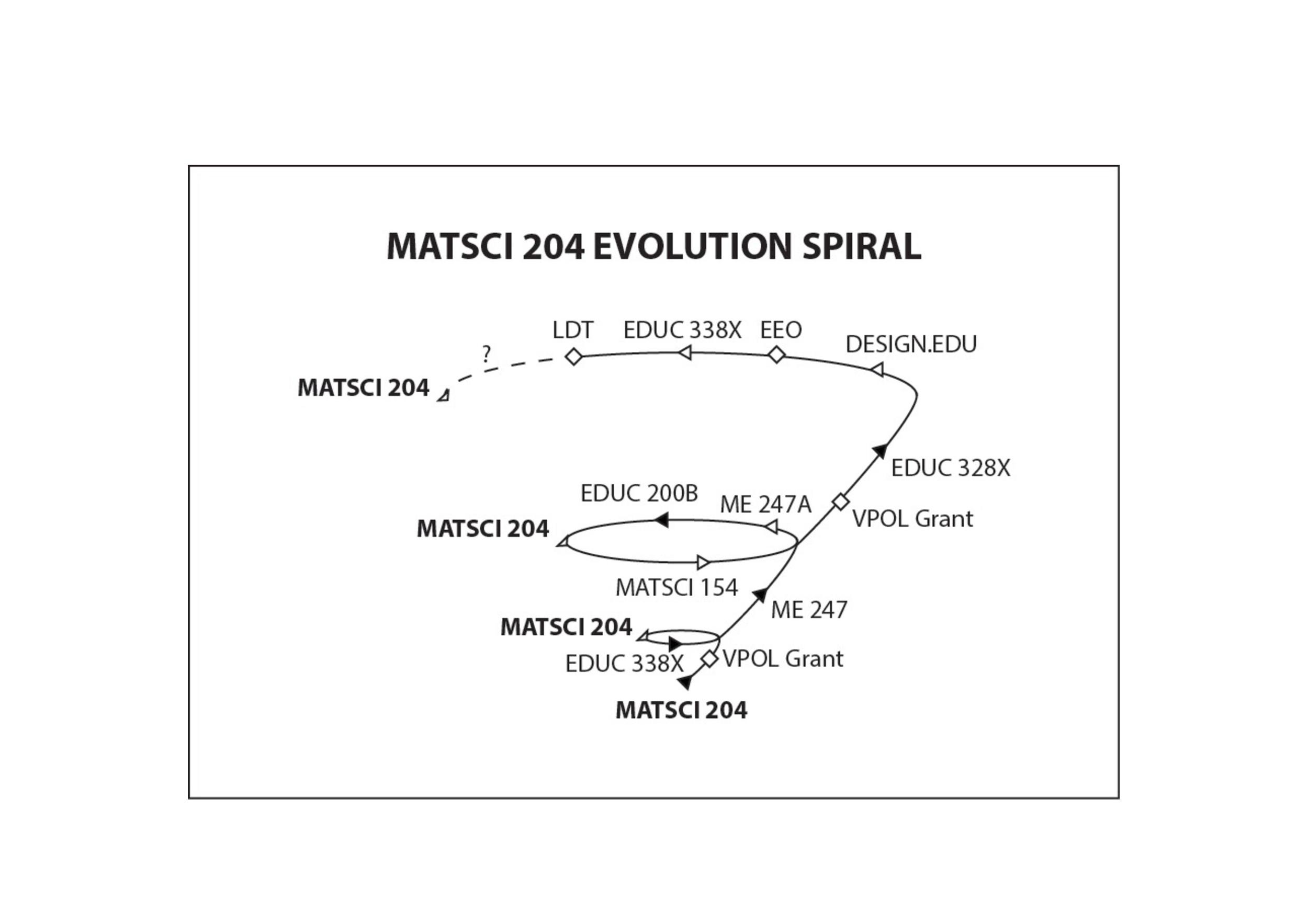

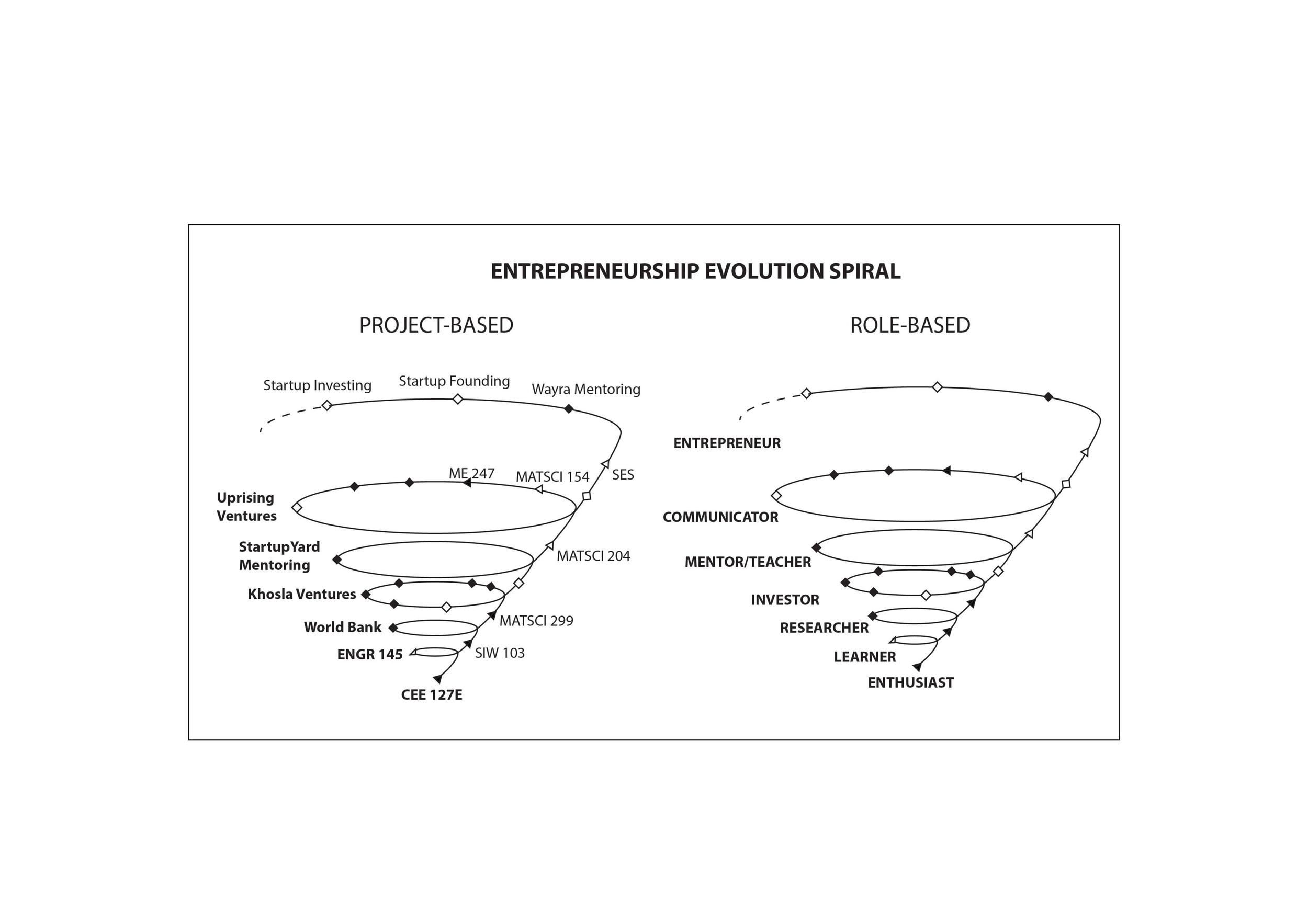

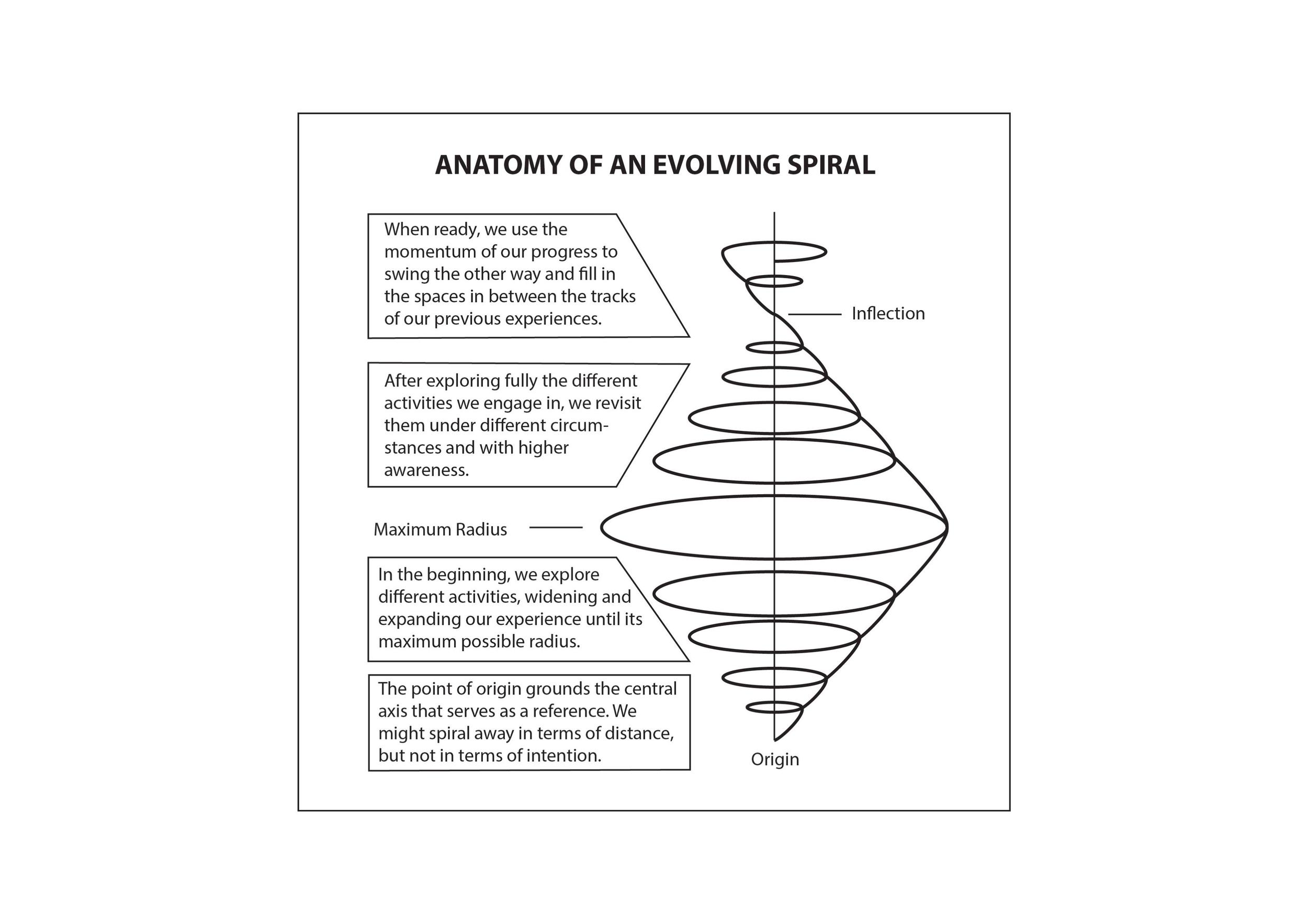

Shown here for the first time, the paper sheets displayed are found pages from Johanes’ initial thoughts and experiments with loops as a PhD student in Stanford’s School of Education. Johanes meticulously documented his own loop and spiral trajectories and synthesized and reflected upon his experiences. As was common in the early 2010s, Johanes often performed work on his computing device and printed results on traditional paper.

Watch Video of Petr Johanes explain his Loops.

Time Traveler reviewing the work of Petr Johanes.

VIEW PETR JOHANES' LOOP + SPIRAL PAPERS GALLERY

Article 55

FROM APPLICATION TO INVITATION

Audio recording circa 2015

In 2015, the Stanford Office of Undergraduate Admissions experimented with an admissions process to replace applications and began to recruit students to come to Stanford rather than requiring them to apply. A phone call from a recruitment officer replaced the lengthy application process.

To find candidates, recruitment officers matched a rigorous, “age-blind” open nomination process with a rotating pool of expert nominators and an anonymous review board. The board cycled annually to ensure that the process was fair and the quality of invitees was high.

By 2016, 10% of students were admitted via invitation. Six years later, Stanford and 28 other universities were using invites instead of applications for the vast the majority of their students.

The impact on high school education and college preparation was profound: students and teachers alike shifted focus away from test performance and on to following personal passion and showing evidence of impact.

Watch Video of Scott Doorley explain Application to Invitation.

Time Traveler listening to a Stanford Invitation

Headphones Recommended